Story & Photos by Larry Bartlett

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of Hunt Alaska magazine.

Papaw was a man of very few words, but when he spoke it was true and razor sharp. I have a memory of him standing up from his garden and pointing over my shoulder at his own backyard sprinkled with overweight family members who were occupying shade with piles of dessert on paper plates. He shook his head in disappointment and said, “Sonnyboy, unless you wanna end up like them (my family) you gotta eat less and move more!” He also claimed, “You can’t learn nothin’ if your mouth is moving,” and my personal favorite, “You gotta ask the right question to get the best answer.” Three sticking points that have contributed to my success in the field and in business.

Papaw wasn’t a hunter or an angler—he was a farmer. He weighed 165 pounds and stood six feet tall until he was well into his 80s. He ate anything on his plate and gave no thought to a balanced macronutrient profile because for him it was all about operating fuel and not excess reserve fuel. If his output was light that day, his rations reflected his workload. But if he got hungry after dinner, he would eat a half-jug of ice cream or finish a tall glass of whole milk depending on the activities of that day and the next one. To him food was the fuel to manage his chore list and to keep his body weight up (not down). He lived disease-free until the very end of his 80s. Today, when it comes to health and fitness advice, I rely on my ancestors more than marketing campaigns and I ask the right questions about my body. I am a professional hunter, I stay field ready, and I am inspired to address the finer points of Papaw’s wisdom to make his success and mine relate to this 21st century audience.

One of my focus areas, besides health and nutrition, will always be to reduce field load carriage (lower the weight and bulk of everything used afield). This strategy has obvious benefits with regards to the efficiency of mobility. My interest in this topic has led me to address the heaviest item on my packing list—food. In order to reduce food weight and bulk, I must first ask the right question. How much food energy (kcals) do I really need to perform competently in the field for 10- to 14 days? The process of answering this question revealed an unexpected plethora of helpful information.

Prior to 2017, no one could say precisely how many calories our bodies burn while hunting in the backcountry. Last year I established a collaboration with Robert Coker, PhD, and his research group at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks to answer these questions. Using sophisticated medical-research technology, we designed a study that determined caloric intake, caloric expenditure and changes in body composition, blood lipids, and fitness levels in middle-aged males during a 12-day Alaska backcountry-hunting scenario. An accurate depiction of this “scenario” is a book I wrote called Float Draggin’ Alaska. The actual data is published in the scientific literature (see: Coker et al., Physiological Reports, 6(21):2018,doi10.148/phy2.13925).

The importance of this high-quality information should not be understated. Food is essential for energy and survival so it’s the last to get trimmed when making weight, but we can only take a reasonable allowance of food to fit within our weight restrictions. High-tech gear or not, it’s the macronutrient (carbohydrates, fat and protein) profile of our food choices that largely determine field performance. As much as 45 percent of expedition-gear weight is food, and that weight costs money to transport and movement energy (kcals) to load, drag, or pack in the field. So, total calorie consumption is one thing to consider, but so is the quality and type of fuel (macronutrient density) that must be understood, skillfully selected and efficiently consumed to help us perform to our highest field potential. Crescendo please! Until now the health benefits of the energy expenditure required to hunt for our own food have been largely ignored. Now we’re getting some real answers.

Based on isotope analysis of urine that traced oxygen utilization needed for energy expenditure, our participants burned an average of 4,326 kcal/day and consumed 2,174 kcal/day over 12 days. This means that these hunters operated proficiently with a net caloric balance of -2,151 kcal/day. This information helps the hunter/adventurer in three ways: 1) how to provide the right nutrients for those demands; 2) how to balance energy expenditure goals in the field with allowable weight loss (can I afford to lose 10 pounds or less than 5 pounds?); 3) how to safely reduce travel weight (and cost) of our single heaviest expedition component—food!

Health Benefits Revealed

The combined stress of the hunting adventure described in our study was responsible for a sustained caloric deficit that resulted in an average of seven pounds per person reduction in body fat. Fat loss included significant decreases in visceral and liver fat (i.e., fat deposits closely linked to metabolic disease). There were also small improvements in overall fitness and LDL-cholesterol (bad type).

In a typical gym-oriented exercise program, it might take three- to four months to promote these beneficial changes in metabolic health. Dr. Coker published an extensive review on this topic ten years ago (see: Hays et al., Pharma Thera 118(2), 2018). By comparison, the effects of repetitive and sustained movement constancy and negative caloric balance on overall health are quite powerful. Think of movement constancy as the amount of time you spend each day moving and working your body’s muscles to meet task-variety demands (standing, walking, biking, rafting, hiking, stacking wood, climbing stairs, loading boxes, lifting children, digging weeds, running, skiing, etc.). This synergy of muscle activity ultimately increases the number of calories we consume (and burn) each day. Whether the bathroom scale reads plus or minus each morning is determined by calorie intake and physical activity—and so is our health and fitness.

Healthy Changes in Physiology

The modern U.S. lifestyle is characterized by the excess availability of foods relative to physical activity/caloric expenditure. More simply, we eat more and move less than we should to stay fit and healthy, and as a whole we are an obese and unfit society. Papaw knew this without a high-school education, and he learned it through movement constancy!

On the flip side, modern living (i.e., excess availability of foods) combined with a relatively low level of daily physical activity enables the habit of eating more and moving less than we burn each day, which is the opposite of what it should be. This excessive consumption promotes an increase of circulating fats (triglycerides) that remain chronically elevated and/or are adopted by the liver. This has proven to be the opposite of healthy because

too much visceral and liver fat has a significant negative impact on core organs which leads to hypertension, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, liver disease, and metabolic syndrome. An undoubtedly unhealthy approach.

The results of our first study (focused on backcountry hunting) has demonstrated that we can transform our physiology through intensive hunting experiences (i.e., increased activity and changes in caloric balance). Even though several long-term exercise interventions lasting three- to four months have resulted in beneficial improvements in metabolic health, our results demonstrate that the negative energy balance linked to backcountry adventure promotes even more rapid adaptations that may protect us against metabolic disease.

Participants’ Field Diet

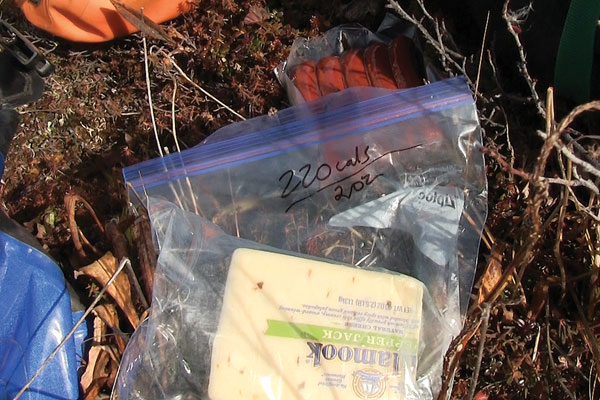

You might question what these hunters were eating during the study. Well, they ate off-the-shelf foods that included dehydrated meals, noodles, jerky, cheese, nuts, peanut butter, bagels, oatmeal, Snickers bars, trail mix, meal-replacement bars, and wild-game meat. This study did not include an assessment of macronutrient density, but we are now collecting data in 12 additional participants (2018 study) that will include this variable.

Basic Conclusions

I’ve often thought about what made our Paleo-ancestors so successful in harsh environments subsisting on meager rations of hard-to-come-by macronutrients—not to mention that length of scroll with a chore list a mile long. I ponder about their lifestyle demands and can’t help but imagine them as survival machines capable of physically disabling large animals with stone tools, and then resting in a boulder-enforced pile of brush. I can only postulate that obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic health problems were not yet pervasive in their culture.

From the results of our study, it seems quite likely that individuals subsisting long ago gained considerable metabolic benefits from the constancy of physical activity and strict rationing of food resources. Back then we hunted and gathered, today we fad diet and buy gym memberships to find a date. Compared to “fitness” business models made popular by short-term workouts that provide marginal time spent burning calories, backcountry hunting promotes an increase in caloric expenditure that is nearly twice the level of dietary consumption. These hunters ate what they brought and didn’t binge snack like many do at the office, and they put in moderate five- to seven-hour work days losing considerable amounts of excess fat. Despite significant caloric deficiency and no post-exercise protein shakes, lean tissue mass and skeletal muscle (measured using x-ray and magnetic resonance imaging) were well preserved. This demonstrates the profound anabolic influence of movement constancy.

Our most recent study conducted during the fall of 2018 included 12 participants (five female and seven male) with an age range of 36 to 61. With the efforts of these individuals, we will soon be able to address the potential for gender variation in these metabolic parameters under the same hunting scenarios. These research participants are average people who hunt, with average levels of fitness, and who have an unquenchable desire to stay healthy and stronger for the next adventure.

Backcountry hunting in Alaska is characterized by physical exertion and negative caloric balance that promotes dramatic improvements in metabolic biomarkers in less than two weeks. While physically-, mentally-, and emotionally challenging, this activity (movement constancy) provides benefits that exceed the modern definition of “exercise.” Despite the health benefits and changes in physiology one can expect with a backcountry hunt, one has to enter the field with a certain level of physical readiness. Papaw was no athlete, but his body remained a pillar of health and fitness his entire life, and he stayed farm-field ready. I can attest to Papaw’s wisdom of “eat less, move more,” and I challenge you to do the same. We are now able to prove this scientifically and make recommendations that will lead to a healthier and more field-ready population of hunters. My parting shot is more of a challenge than a transition: Get outside, Alaska, and if you eat it, burn it!

Larry Bartlett is a combat veteran, author, film maker, and hunting innovator whose professional mission is to collectively raise the health and intelligence of his community. His background includes 12 years in the U.S. Army (combat medic and licensed nurse), as well as 20 years as an Alaska hunting authority and owner of Pristine Ventures, Inc. His latest entrepreneurial branch will serve in areas of health, fitness, and nutrition DBA Industria Imperium with Dr. Trey Coker, PhD.